As ABC began planning for the 2000 NFL season, then president Howard Katz needed sizzle for Monday Night Football. He’d joined the network the previous spring and hadn’t wanted to fiddle too much with a 1999 season that would end with a Super Bowl on his air. But his first few months only clarified how MNF was losing its luster. Ratings were down. Buzz for games wasn’t where it needed to be. One way or the other, change was coming.

The first change Katz pursued was luring legendary producer Don Ohlmeyer out of retirement.

Ohlmeyer agreed to come on one condition: He’d be working from a clean slate. So ABC cleaned house, letting top producers and directors go, retaining only Al Michaels from the front-facing broadcast team. From there, Ohlmeyer cast MNF like he would a sitcom.

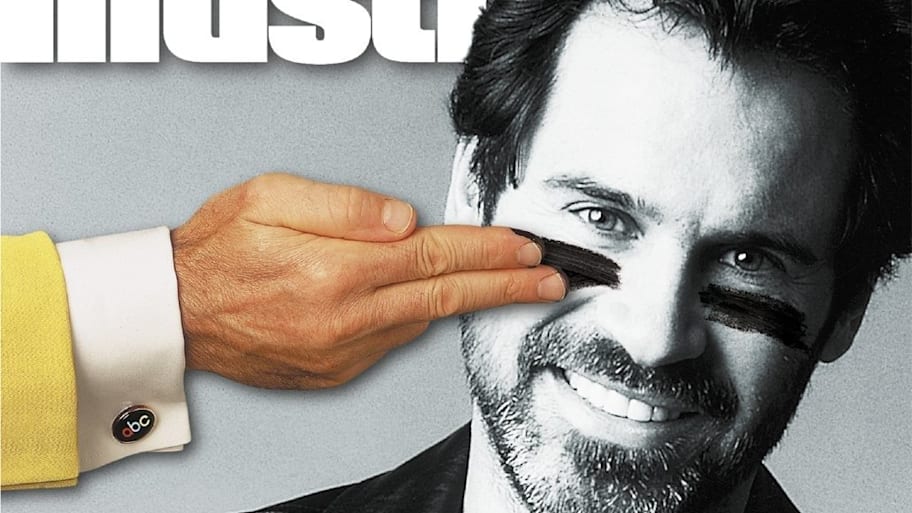

ABC interviewed and auditioned a ton of people. Ohlmeyer was looking for a bold swing to turn momentum, and found that swing in comedian Dennis Miller.

Miller was 46 at the time, and a massive star. He’d been on Saturday Night Live. He’d had a syndicated late-night show. It was the first time since Howard Cosell that ABC hired someone into the MNF booth without a real football background, doing so with the hope it would pull in the casual fans and help make the stand-alone games feel big again. ABC paired Miller with Michaels and former Chargers quarterback Dan Fouts to fill out what was (on paper) a well-rounded team.

It lasted two years. Ohlmeyer left after the first season. The iconic John Madden became available after the second season. ABC landed him, and that was that for one of the more outlandish experiments in sports television history.

It was also indicative of where the NFL was in Y2K.

The 2000 season was a strange one. The Ray Lewis murder accusations from the Atlanta Super Bowl of January 2000 hovered all year. The Cowboys’ and 49ers’ dynasties had expired. The Brett Favre Packers had a first-year coach, Mike Sherman, who replaced the one-and-done Ray Rhodes. The Patriots and Colts, teams that would dominate the decade to come, hadn’t arrived yet. Jim Mora was still Indy’s coach, Bill Belichick was just hired in Foxborough, and Tom Brady was a rookie just trying to make New England’s roster.

The July 3, 2000, cover of Sports Illustrated had a black-and-white photo of Miller with an outstretched arm designed to look like Cosell’s smearing eye black on his face.

The headline: Can Dennis Miller Save Monday Night Football?

In retrospect, the question was probably the wrong one to ask. Because just as MNF was looking to rediscover its magic, the NFL was trying to find its footing after coming out of the prosperous 1990s.

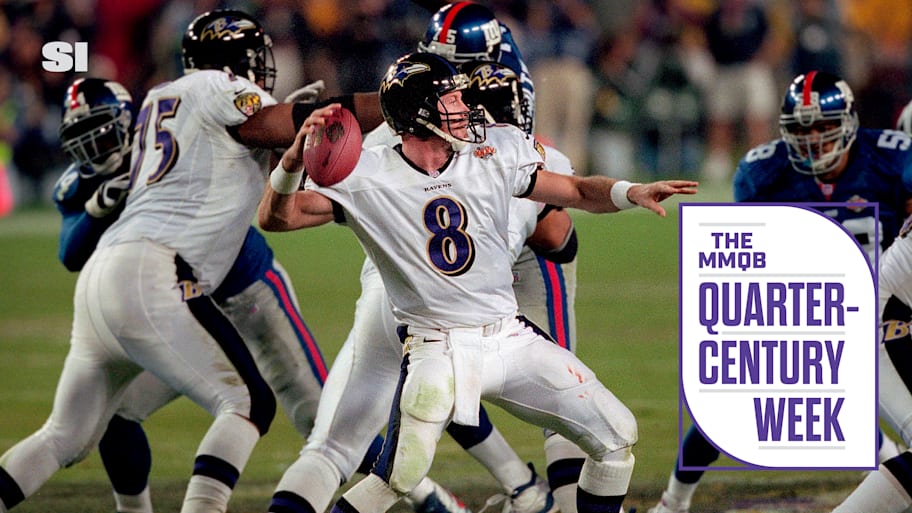

The Super Bowl to finish the 2000 season showed it. In one corner, you had a Baltimore Ravens team still searching for an identity as a franchise, in its fifth season after moving from Cleveland and still looking for its first trip to the postseason. In the other, there were the New York Giants, whose most remarkable moment from the regular season was a press conference rant starring the late Jim Fassel, pushing his “chips into the middle of the table.”

Both had reclamation projects at quarterback. The Ravens started Trent Dilfer, who’d washed out of Tampa Bay six years after the Buccaneers took him in the first round, and didn’t even seize the starting job from Tony Banks until midseason. The Giants had Kerry Collins, who’d battled a drinking problem after early success as the Panthers’ first-ever draft pick, then bounced from there to New Orleans and finally New York.

“The league was in this void of great quarterback play,” then Ravens coach Brian Billick explains. “We were out of the [John] Elway, [Joe] Montana, [Steve] Young, [Troy] Aikman era. We hadn’t arrived yet with the Brady, [Peyton] Manning group. So, yes, at the time, playing great defense, running the ball, you could compete at that level. Now, it’s almost like if you don’t have a Hall of Fame quarterback, or at least a real good one, you don’t have a chance.”

Within that void, the Ravens became a statistical outlier in a variety of ways.

There was, of course, an excellent defense anchored by Lewis, Peter Boulware, Michael McCrary, Tony Siragusa, Sam Adams, Rod Woodson and Chris McAlister. That unit allowed the fewest points ever in a 16-game season (165), the fewest rushing yards ever (970) and led the NFL in takeaways (49).

But there was another side to it, too. The Ravens failed to score a touchdown in October—and played five games in that month—which led to the Banks-Dilfer switch. And in their 34–7 Super Bowl win over the Giants, Baltimore had just 244 yards and 13 first downs. Two of the game’s five touchdowns were scored on kickoff returns, and another came on a 49-yard pick-six late in the third quarter that blew open what was a 10–0 game.

Then, there was the Lewis saga.

“We started the season with that, and it was us against the world, with how they came after Ray,” Billick says. “And it went all through the season, particularly once we went on the road. Even if the story died off a little, on the road, before every game, you pick up the Sunday paper, and there’s a picture of Ray in an orange jumpsuit.”

That Ravens team will be forever remembered for the defense Lewis anchored, and the foundation that team forged behind Billick, defensive coordinator Marvin Lewis and GM Ozzie Newsome, which remains with the franchise in many ways to this day. But Billick wouldn’t deny it was also a group uniquely qualified to exploit the void explained above.

“We weren’t even favored to win the division,” Billick says. “We’d come off an 8–8 season, our first year there. … I knew we were good defensively; it was a very special group. But I’d be lying if I said I knew we’d be that special.”

Of course, as good as the Ravens were, the void was part of the equation, too.

“I don’t really remember playing anyone and saying, Oh s---, we gotta play them on offense?” former Panthers, Broncos and Bears coach John Fox says now, a quarter century after he was the defensive coordinator for that Giants Super Bowl team. “If it was anyone, it was probably Minnesota.”

So preparing for those Vikings in the NFC title game, Fox had made the off-hand comment to then Giants offensive coordinator Sean Payton that Payton’s unit was going to have to put some points on the board to keep up with Minnesota. It seemed logical at the time, with Daunte Culpepper in the midst of a breakout year, and Randy Moss, Cris Carter and Robert Smith at his disposal.

Still, days later, walking in for halftime at the old Giants Stadium, given how the first half went, with New York up 28–0, the young offensive mastermind was gonna get his shot in.

“Twenty-eight enough for you?” Payton asked Fox.

“I don’t know,” Fox responded. “They get the ball to start the third quarter.”

The Giants (somewhat shockingly) won 41–0, but the underlying point was that even an offense among the NFL’s most feared could be had. And a look down the list of top offenses from that season further illustrates the point.

The “Greatest Show on Turf” Rams led the NFL in scoring and total offense, but were transitioning from Dick Vermeil to Mike Martz, and their defense had collapsed. The Broncos, under Mike Shanahan, were second in total offense, having rebounded out of their post-Elway crater of a 1999 season, but had Brian Griese and Gus Frerotte at quarterback, and were leaning on Mike Anderson to carry their vaunted run game. Manning’s Colts were third. The Jeff Garcia–led Niners were fourth. The Vikings ranked fifth.

It should make sense, then, that the MVP race was jumbled—but won by a Ram. Hall of Famer Marshall Faulk got 48% of the vote, after rolling up 2,189 scrimmage yards and 26 touchdowns, buoying the offense through the coaching change and a raft of injuries that contributed to the defense’s demise, and five games missed by fellow Hall of Famer Kurt Warner.

Still, in the midst of a decidedly old-school year, the Rams (more quietly than the championship season before) continued to set the tone for where football was headed.

“We broke the norm in that we could run on any down or throw on any down,” says Faulk. “First-and-10 didn’t mean run. We pushed norms—third-and-1, fourth-and-1, we’d go deep. We were very unconventional. Before that, aside from the run-and-shoot teams, if you threw the ball 25 times in a game, that meant you were losing. Football turned into that if you didn’t throw it 25 times in a game, you were losing. And that’s where the game is today.”

As it turned out, with a revamped defense and Lovie Smith hired to run the unit in 2001, the Rams would go back to the Super Bowl after their uneven season of 2000. No one would’ve guessed, after 2000, which team that they’d meet when they got there.

If there was a team-building effort that landed above the proverbial fold back in the newspaper days of 2000, it was happening in Washington. The team had won the NFC East in 1999 under Norv Turner, in Daniel Snyder’s first year as owner, and Snyder was pushing his top football exec, Vinny Cerrato, and Turner to go all-in on the season to follow.

Money was no object. “The one thing I have is cash,” Snyder told Cerrato.

An avalanche of moves followed. Washington had the second and third picks in that year’s draft, courtesy (in part) of the Ricky Williams trade the year before, and took Penn State linebacker LaVar Arrington and Alabama tackle Chris Samuels. Future Hall of Famer Champ Bailey was already in Washington, as was quarterback Brad Johnson. The team splurged on the aging Bruce Smith, Deion Sanders, Mark Carrier and Andre Reed.

It also poached Jeff George from the Vikings, who were making way for Culpepper, picked in the first round the year before, to take the quarterbacking reins. Different from the other moves, though, that one came from above.

“We started 6–2, and then we had kicking issues, and that killed us,” Cerrato says. “But the problem for us was when Jeff came in. Brad was coming off a Pro Bowl season. There was no need to have Jeff George there. That was strike one. … The other guys were good. We had a great coaching staff. You draft Chris and LaVar. But you gotta do what the owner wants to do, that was his style.”

Washington lost four of five. Turner was fired. Johnson was benched. The team next made the playoffs five years later.

Meanwhile, 400-plus miles up I-95, another team took a far more conservative approach. In a league that hadn’t yet fully grasped the salary cap, six years after it was first instituted, one franchise started to draw a blueprint for how team-building should be done. Plans for it were laid in the Jets’ facility in the late ’90s, where then defensive coordinator Bill Belichick and pro scouting director Scott Pioli had connected offices and melding philosophies.

They’d discussed—before their high-profile departure from the team in January 2000, which led to a court case, Belichick’s resignation and the Patriots having to fork over a first-round pick to hire him—how leaning into big-money signings like Washington did was the wrong way to go. Instead, if they were to build their own team, they thought finding players that fit specific roles for specific coaches, programs and systems would be far more efficient.

The problem was, when they got to New England, they were $10.5 million over the $63.2 million salary cap, with just 41 players under contract, and Drew Bledsoe’s monster extension essentially arranged, agreed to and foisted on the new guys.

“It was going to be a challenge, but we had a plan,” Pioli says. “We’d studied the types of players that Bill had success with.”

Tom Brady was drafted that April with 199th pick. That was the biggest piece to the puzzle. Of course, no one saw it that way when it was put in place. But if that was largely a stroke of luck, the way the decks were being cleared wasn’t any mistake.

The Patriots let go of decorated veterans such as Ben Coates and Bruce Armstrong. They signed 27 rookie free agents. There was a point in the season where, for cap reasons, they only carried 51 players on their 53-man roster. While they wanted to be competitive to establish credibility, Belichick and Pioli weren’t going to sell away tomorrow for the sake of today. They started the season 2–8. A modest 3–3 finish bumped them to 5–11.

The following March, with clean financials, the plan was in motion, with 23 free-agent fits found and only $2.5 million in signing bonuses doled out. Anthony Pleasant, Bobby Hamilton, Roman Phifer, Antowain Smith, Mike Compton and Mike Vrabel were among a group the Patriots saw as players who’d fit schemes that were different from what most of the rest of the NFL ran. They joined the Bill Parcells–built core of Ty Law, Troy Brown, Lawyer Milloy, Tedy Bruschi and Willie McGinest. Brady emerged. The rest is history.

“We’d made the determination that just spending money didn’t necessarily mean finding good players—those things aren’t equal,” Pioli says. “Having the right player for your system, and right player for your head coach, and the players that are willing to do what it takes in your organization, that stuff matters.”

Which is why, while one team blew everyone away in the spring of 2000, the team that was quietest of all was setting the stage to turn the NFL world on its head a year later—and become the preeminent team of the two decades to come.

(How things played out for Snyder and his team had an impact, too.)

The Patriots’ strategy wasn’t the only harbinger of where things were going in 2000.

Despite the deflated nature of offense league-wide, and the dip in overall quarterback play, there were outsized numbers that came from the season. The Rams’ 7,075 yards from scrimmage, and 5,232 yards passing, split between Warner and Trent Green, broke 26-year-old NFL records by the Dan Marino Dolphins. Terrell Owens had 20 catches in a game, breaking a 50-year-old record. Corey Dillon had 278 rushing yards in a game, breaking a mark by Walter Payton in the late 1970s.

Yet, the two teams fighting for the Lombardi Trophy at the end came in with top-five defenses and, more notably, without top-10 offenses, and left it having set records for fewest combined yards (396) and most punts (21), and tied a record for fewest first downs (24) in a Super Bowl. Brian Griese (!) was the league’s highest-rated passer. Marvin Harrison and Muhsin Muhammad led the NFL in catches. And 10 players topped 1,300 yards rushing.

Again, it was a weird year.

And then there was Miller, calling the action from above. The impact was similar to the Washington splurge. Ratings slipped a little further. The plug was pulled after two seasons. The Madden-Michaels booth was solid, as anyone would’ve expected. But MNF’s shelf life, as the NFL’s premier television franchise, was running thin.

In 2006, NBC, which lost the AFC package in the late 1990s to CBS, was getting back into the NFL broadcasting game—with a catch. They’d get Sunday Night Football, with the league planning to turn SNF into the big game of the week, while making MNF its sidecar.

So that feel Katz had that MNF was losing its magic in 2000 was proved correct.

It just took a weird year to show it.

That wasn’t the only weird thing about 2000 in the NFL, of course. Or the only thing that the league had to learn coming out of that year.

This article was originally published on www.si.com as The 2000 NFL Season Was a Strange Year Wedged Between Two Eras.